Irish Haiku

"To separate the truth from the truism requires hard thinking and deep trawling, both of which occur in heady profusion here ... The essay, in Chris Arthur's hands, proclaims its outsider status, its subversive momentum, its effortless inclusivity and freedom from trammels of the imagination, attaining an embodiment which is civilized, idiosyncratic and rare."

Patricia Craig, Times Literary Supplement, 16 Sep 2005

Irish Haiku ranges from a 40-page meditation on history, conducted via an exploration of the mysterious act of violence which left a son dead and his father shot in the face (the so-called "Lisburn Tragedy" of 1898), to a short and lyrical account of how little we remember of what people say to us. "Witness" starts from meeting a terrorist in a second-hand bookshop; "Water-Glass" is further evidence of Arthur's fascination with the way in which local history is so closely entangled with happenings on a much wider scale; "How to See a Horse" considers how much more there is to this apparently straightforward task than just looking at what's immediately before the eye. Like its two sister volumes, and as its name suggests, Irish Haiku makes reference to haiku poetry, the great minimalist verse form of Japan which is so imbued with the spirit of Zen Buddhism. Haiku have been a significant influence on Arthur's writing.

Here's how the Foreword, "Beginning by Blackbird", begins:

Instead of any words at all, I would rather start with a blackbird singing in a County Antrim garden. Whether at dawn or dusk is of no matter, so long as the light is minimal enough to veil the detail of the landscape, still the restless eye, so fixing attention on the liquid resonance of this clear-sung scale, letting it, if only for a moment, hold consciousness spellbound in delight at the pure perception of this ancient lilting music. Sounding such a tuning fork might help to counter the expectations that attend beginnings, those most artificial of literary devices. Beginnings promise the order and progression that we crave. Their wordy lifelines suggest the existence of sufficient anchorage to reel ourselves towards habitable meanings from whatever fixed points of apparent genesis they seem to offer. They give the impression that sentences can be so ordered as to still the oceans of complexity and mystery that underlie us, subduing them into linear solidity and the believable fiction of logical progression from A to Z. But language falls upon the waters like autumn leaves spangling the blackness of a miles-deep pool with a patina of reds and golds, creating only the illusion of a surface we might walk upon. The beginnings it can be used to craft provide no more than a film over what is fathomless... A blackbird's solitary singing should not create any expectations of what comes next, what went before. Like a clear bell in a meditation hall, it just punctuates the silence, focusing the mind on what passes before it now, this moment that will never come again.

Reviews

"He is an essayist whose fine perception of essential things and ability to expose these things in a vibrant way combine in the production of beautiful pieces of literature ... Arthur never fails to make his reader think, and think deeply at that ... In Irish Haiku Arthur recovers the tradition of the meditative essay, brilliantly developed by the North-American Transcendentalists — and it is no coincidence that the book's epigraph is from H. D. Thoreau ... The whole book is embedded in a Zen Buddhist atmosphere — or Zen aesthetics; it is impregnated by a poetic vision similar to that of haiku-master Matsuo Bashô ... Arthur's essays try to catch deep and revealing moments, always with a striking directness — a process of clear seeing that triggers a temporary enlightenment. Arthur's essays excel at many levels, principally because they draw from eclectic sources. Many of his essays cite stories or beliefs from Buddhism and Hinduism, creating an interesting mixture of Europe and Asia ... Arthur, whose prose has been compared to Seamus Heaney's poetry, beautifully transforms individual experiences into universal ones; in his texts, as this trilogy proves, the specific cultural milieu of a specific experience opens itself up to acquire extraordinary — metaphysical, critical and historical — dimensions."

Luci Collin Lavalle, "Vistas Within Vistas — The Meditative Essays Trilogy by Chris Arthur", Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies, Vol.7 (2005), pp.281-286

"The book I have in front of me as I write this is intelligent, perceptive, and moving. It is meditative, unpretentious and written with the emotional precision of great poetry. Its author is from Northern Ireland, but he studied at two universities in Scotland and now teaches in Wales. But even though he has written two equally luminous books already, you won't have read a review of them in any other British newspaper. Why not? There's one simple reason. They're essays. In the country of Hazlitt, Lamb, Stevenson and Orwell, we no longer know what to do with essays ... So what are we missing? In a word, reflection. The kind of thought that doesn't automatically spring up in response to a deadline, that is idiosyncratic, subversive of easy certainties. Chris Arthur's essays offer more, even, than that. They explore the minutiae of life as well as its depths ... Whatever his subject, Arthur uses language that pares away at the core of experience with a care and precision we have grown unused to, chasing away clichés of thought as well as of phrase. Even in a rare genre, he's a rare writer indeed."

David Robinson, The Scotsman, 20 Aug 2005 (Page 38 of Critique, the paper's literary magazine. Robinson is The Scotsman's Literary Editor. This page can be accessed online here — it's part of a feature called "Passions" which pairs someone's "hate" with someone else's "love". You need to scroll down through Mark Cousins' rant against Jack Nicholson to reach David Robinson's encomium on essays.)

"Just as the haiku illuminates a passing moment with a feeling of its sacredness, Arthur's essays are concerned with minor ephiphanies ... [his] essayistic retrieval ... bestows majesty and gravity on what appears on the surface to be inconsequential. Despite the seemingly pessimistic prospect of humanity's absurdly short history and relative lack of importance within an expanding universe, Arthur imbues the very transience and contingency of the ordinary human life with vitality and meaning. While the obvious literary comparison to draw is with Joyce's moments of epiphany, I think the conjunction of the local and the universal that one unearths in these essays more closely resembles the work of [John] MacGahern ... Arthur knocks the walls that assign historical hierarchies to the grand and the global, and argues that there is poetry to even the most banal of lives and chance occurrences."

Eoin Flannery, "Everyday Ephiphanies", The Irish Book Review, Vol.1 no2 (2005), p.44

"Chris Arthur's marvellous essays get to grips, evocatively and obliquely, with ideas of ancestry, continuity, attitudes and allegiances — all in a volatile Irish context. Irish Haiku is the third volume in a series which began with Irish Nocturnes (1999), and continued with Irish Willow (2002). The essay as a 'radically independent' literary form, going its own way and garnering all kinds of insights as it goes, suits this author's singular and erudite leanings. Taking a wide view, as he does, he can't escape an awareness of endless complexity underlying every moment and every perception; but, far from fostering vagueness, this results in unimpeachable precision. Not a pinning down, indeed, but an opening out into realms of speculation and contemplation determines the essays' orientation. Reading Arthur, you might find Louis MacNeice's phrase about "the drunkenness of things being various" springing to mind, only to realize that "drunkenness" is not appropriate here. Far from proceeding in a haze of inebriation, these essays gain their effects from an absolute sobriety and delicacy of approach."

Patricia Craig, "Incidental Illuminations", Times Literary Supplement, 16 Sep 2005

"'My concern here,' Chris Arthur writes midway through this third collection of personal essays, 'is with the insidious process by which the world's strangeness and mystery becomes so swaddled that our wonderment at being atrophies and dies.' Readers of the earlier collections, Irish Nocturnes and Irish Willow, will recognize Arthur territory: insistence on the "wonderment at being" energizes the circling of consciousness which his essays enact and exemplify ... Arthur's style is his own and his concern as a writer is with the dubious nature of representation; in this lies his claim on our attention. [His] unique place in Irish writing is grounded in his deep and abiding affection for the Ireland of his childhood and youth ... and in the transcendental elsewhere, which in its own way circles back through literary echoes and exiled, religious, searching ... He approaches history not through political narratives or ideologies but through 'the weight of the actual, the solidity of what once was, the authenticity of what happened moment-by-moment in all the heavy fullness of its intricate, unreachable, densely entwined detail.' ... At the heart of Arthur's style and accomplishment is a deeply compelling need to imagine a space without hatred, fear, bigotry and violence. His essays continue to be a unique testimony to a very particular kind of Irish exile."

Denis Sampson, An Sionnach: A Journal of Literature, Arts, and Culture, Vol.1 no.2 (2005), pp.151-153

"In his third book of prose reflections, Chris Arthur reminds us that "essay derives from essai, to experiment", and uses the term 'Irish haiku' to define his distinctive approach to 'creative non-fiction'. Strongly influenced by Zen Buddhism, he cites haiku as the supreme verbal testimony to "seeing what's here, right now". Yet though this poet's prose is frequently epiphanic in haiku-like moments, he does more than see (and show): he philosophizes. Thought is the natural consequence of perception in these ten subtly interrelating essays; they adopt gradually Joycean structures in their shifts of focus, but represent less streams of consciousness, being more like meditations ... One of Arthur's most appealing strengths is his ability to create atmospheres which, though gentle, are tacitly dark, as he shifts between remote cottages, graveyards, canals, shops, gardens, and streets. Irish Haiku is manifest with a sense of stillness; partly because the setting is essentially the past. Yet, Arthur's Ulster remains unsentimentalized. His uncompromising honesty and recognition of present concerns reflect the Zen-like clarity of his outlook, as well as that of his style ... Conflict is a prominent concern in these essays, but Arthur addresses it with wisdom and lucidity ... Arthur is a writer who demonstrates and promotes these virtues; he is also charismatically knowledgeable on an eclectic range of subjects, artistic, historical, philosophical and spiritual. His quotations mark his influences: Voltaire, Adorno, R.S. Thomas and Buddhist scriptures ... This book is highly recommended to anyone interested in the essay as a form, and essential for readers wishing to follow developments in Anglo-Irish writing at the start of the twenty-first century."

James McGrath, Estudios Irlandeses, Vol.1 (2006)

"Chris Arthur's Irish Haiku is a series of prose reflections on life, the universe and everything. The book, handsomely presented by the Davies Group Publishers, follows Arthur's earlier Irish Nocturnes and Irish Willow. In this new book Arthur draws on events and stories from his Co. Antrim childhood as well as from the gleanings of his own extensive reading in order to ruminate on the fleeting nature of existence and the mystery of what constitutes humanity. The collection of essays which ensues is compelling. The opening essay 'Obelisk' is an engaging interrogation of the fluid nature of memory and narrative. Part detective story, part family history and part philosophical discussion, the essay ponders the reasons behind the existence of multiple versions of a family tragedy. The sympathetic use of contemporary newspaper extracts brings historical events to life in a manner reminiscent of Angela Bourke's The Burning of Bridget Cleary. Arthur's careful use of language makes for memorable images. In 'Safety and Numbers' a child with a mental handicap whom he had deemed an intrusive presence is later to 'lodge in [his] mind like a permanent splinter'. His honesty in assessing his own ambiguous reactions to what he terms 'the gridlock of [his] heritage' makes his a fresh and interesting voice on the North. Arthur's eclectic reading yields surprising nuggets. If the unwieldy architecture of his musings sometimes proves challenging, the thoughtful teasing out of the various intriguing questions posed ('For how long should we remember the dead?' 'How much of speech do we actually remember?') ensures that the extra effort involved in following a meandering train of thought is worthwhile. The memorable final essay 'Swan Song' successfully draws together many of the various strands of Arthur's narrative in order to reflect on the difficulty of writing about the loss of a son. In this essay, as in the collection as a whole, Arthur's insights into the tensions of his own belief system and the passion of his own creative reaction to the 'crazy buoyancy of consciousness' provide the real interest."

Roisin NiGhairbhi, Irish Studies Review, Vol.15 no.4 (2007), pp.530-531

"Chris Arthur's essays are as artful and literate as Hazlitt's and Lamb's, but they are much more narrative in mode and more personal ... the narrative method becomes predictable as one reads, and it is both delightfully postmodern and digressive in a way that returned me to the more leisurely digressive novels of Sterne and Furphy ... It is simply a pleasure to watch a well-stocked mind move around its narratives with few restraints on its operation and modes of discourse. ... The essayist, especially the intelligent morally relativistic one, operates within a genre which is self-conscious, lacking in rules and generative of its own, and which values using language precisely and exactly, and poetically. His method is normally to focus on a narrative, or character-based centre, and to spin off from that into meditative considerations, often by locating a tiny event in time and space in order to focus on the paradox of meaning-making in a context of meaninglessness in the vast scheme of things. In Chris Arthur's world, history goes back to palaeogeology and the big bang, as for example in the essay 'Miracles', which circles back from a 32-million-year-old otolith (fossilized whalebone), via Brother Erskine's strategic and moral silence about his desert war experience and his eloquent challenge to a preacher's fundamentalism, to 'tribal otoliths of pathological dimensions', and he has in mind the politico-religious dualisms which create fissures in the north. Every element in this essay has to be there, is justified, elegant and spare in its elaboration of its own form. His centrifugal spin-offs can lead to some surprising places: for example, from a prized Vulture's egg, to memories of his mother's egg-preserving technology, and this in turn serves to explain not only the limitations of her method, but also the opacity (a metaphor which also does double-service) of the workings of memory. It's a tortuous route and typical of many of the essays, but somehow justified and illuminating, and again, it is fundamentally different from conventional fiction-writing, and for its sheer elegance of design and expression, literary and literate. ... This is a superb post-colonial text, as well as being one with much to say about how the sacred might be redefined in a genuinely pluralist world, a world in which the terms sacred and secular would not be separated by a drawn sword. It offers insights into a life lived richly and thoughtfully in a particularly interesting place and time. Congratulations to the publishers for picking up so unusual a text and for discerning its socially progressive agendas."

Frances Devlin-Glass, Australasian Journal of Irish Studies Vol. 6 (2006/7), pp. 139-144.

"What we have in Irish Haiku is a supreme distillation of themes that consume Arthur: time (past, present, future), memory, and language. Of these it is language that is most celebrated in these pages ... A good book of essays is enjoyable, in part, because essays tend to be of a certain length — we understand the time dimension before we open the book. We also (if the essay is good) anticipate coming away from the experience — provoked emotionally, intellectually, politically. Good essayists know how to grab the reader immediately — they understand the importance of the essay's boundaries. An agreement exists between reader and writer based on the essay form. Arthur brings us into his world via these moments in "essay" time and humbly asks that we allow him entry into our individual inner landscapes. He pardons himself while, with a surgeon's skill, he moves the reader's emotional sinews to reach the fleshy core — as it truly is, not as we might like it to be — and leaves us turning the pages of Irish Haiku in our minds — even after we've put down the book.

Madeleine Beckman, The Literary Review, Vol.51 no.4 (2008), pp.241-243

There has also been comment on Irish Haiku in more popular literary sources:

- An unsigned review in Due North, Vol.2 no.1 (2006), p.42, says: "This is exceptional literature."

- In the Irish Emigrant's "Bookview Ireland", the reviewer — Pauline Ferrie — notes: "Over the past ten years I have had, perforce, to learn the art of speed reading but there are some books that cry out for a more measured response, and the works of Chris Arthur are an example." (See here.)

Irish Haiku can be bought from:

"If an essay doesn't at some point surprise the writer, it probably isn't worth writing."

Lydia Fakundiny

Contents

- Foreword: Beginning by Blackbird

- Obelisk

- Safety in Numbers

- Miracles

- What Did You Say?

- How to See a Horse

- Getting Fit

- Witness

- Water-Glass

- Malcolm Unravelled

- Swan Song

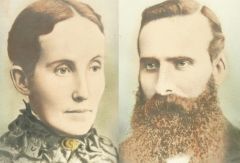

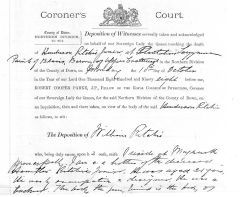

Catherine and Henderson Ritchie, two of the key characters in the mysterious tragedy discussed in "Obelisk".

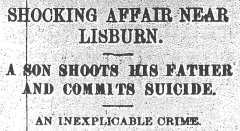

The Belfast Evening Telegraph of October 10 1898 reports the "Shocking Affair Near Lisburn". Click to expand.

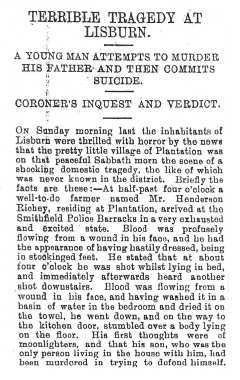

The Lisburn Standard purports to give "the facts" about this "Terrible Tragedy". Click to enlarge.

Hoburn Hall, the farmhouse at Plantation, County Antrim, where the events described in "Obelisk" happened. The farmhouse has since been demolished.

The start of William Ritchie's deposition regarding the death of his brother. Click to enlarge.

The painting that provides the central point of reference for "How to See a Horse," originally published in Orion magazine.

The fossil "otolith" — with a watch for scale — sitting on a willow-pattern plate. "Miracles" begins with this ancient remnant.

Three views of Bachelors' Walk in Lisburn, central to the walking meditation in "Water-Glass".

Repeated crossings of the Irish Sea, particularly via Larne in County Antrim to the Scottish ports of Stranraer or Cairnryan, have been a feature of the author's life. The symbolic potential implicit in sea crossings is a recurrent theme in many of the essays. The pictures, taken from the European Highlander ferry, show a calm sea just off the coast at Larne.