Irish Willow

"I have just finished reading Irish Willow, a book of essays that is so thoughtful and perceptive (think Seamus Heaney's poetry in prose) that I wanted to underline whole passages, and yet so beautifully produced that I didn't dare."

David Robinson, The Scotsman, 16 Mar 2002

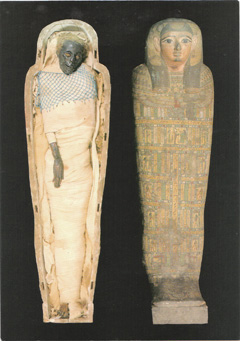

Irish Willow continues Chris Arthur's explorations of family, memory, place, time, loss and meaning. The essays' focus is diverse — they look at photographs, taxidermy, prejudice, exile and homesickness, train sounds, an Egyptian mummy in the Ulster museum, the way two elderly aunts sit in their contrasting manners in an old coastguard station in Donegal with spectacular sea views. But underlying every topic is a concern for the elemental aspects of human existence.

The book begins with a short Foreword, "Falling Through". These are the opening paragraphs:

The image that keeps coming back to me, when I try to think of ways to explain what this book is about, is of a little girl, no more than three or four years old, falling into a pond. "Falling" doesn't quite catch what happened, though. It suggests she stumbled at the edge, lost her balance, tripped and toppled in. In fact, she simply walked onto the pond, not noticing it was there at all. Then, to her complete surprise, she fell through what she had supposed was solid ground. Covered with a dense growth of weed, the surface of the pond was an opaque and seamless green, an unbroken meniscus of tiny interlocking leaves masking the fact of water. She obviously saw it as no more than an extension of the neatly cut lawn in which it was embedded and was drawn to explore so smooth and bright a patch of grass lying within its enticing circle of white marker stones.

The scene replays in my mind in slow motion and freezes at the point where the solidity of her world turned liquid without warning and the surface green of the pondweed changed to black as the water beneath it was revealed and she vanished momentarily from sight. The incident happened at a kindergarten sports day on a long-vanished summer's afternoon in Lisburn, County Antrim. She was soon fished out, dried and comforted. Most people didn't even see what happened. The pond was in a quiet corner of the garden and attention was on the races being run. The cheering blotted out her wails.

At first, I was uneasy about allowing something so trivial to front a book. It seemed calibrated on too small a scale to shoulder the weight of the pages that follow, or to measure up to the task of hooking the reader's attention, holding it, then drawing it into the slow unraveling of sentences that reading demands. I was conscious of the fact that it lacked any hint of those lurid hues that colour so many literary beginnings now, creating expectations that are unlikely to be satisfied by a little girl's harmless misadventure. And yet, despite the absence of any obvious thrill or drama, for all its failure to entrap attention at the outset with voyeuristic promises of sex or violence to come, the more I thought about it and weighed up other more strategic openings, the more I came to know, with a certainty that wouldn't brook alternative or invention, that this was the right place to begin.

Irish Willow is a series of accounts of fallings through. Starting always from the familiar, the small scale, the known — hands, photographs, a country lane, trees, the sound of trains — I try to show how in such seeming shallows there are truly awesome depths. According to Sven Birkerts (writing in The Gutenberg Elegies), language is "the landmass that is continuous under our feet and the feet of others and allows us to get to each other's places." I hope that the word-maps I've attempted to draw here will allow others to walk onto some of the patches of pondweed that have surprised me, so that they too may feel them giving way and opening into unnoticed waters.

Reviews

"The book is a fascinating read for anyone interested in the Irish experience, especially the Ulster Protestant experience, in that it explores questions of identity from a non-Catholic perspective. While there are strong reminders of Seamus Heaney in the volume, especially with regard to the linking of moods with landscapes — Arthur meditatively stakes out his own personal space, and reclaims the landscape for the Protestant sensibility, describing a terrain that is at times as immanent with a sense of the numinous and sacred as any Heaney landscape ... Irish Willow is an engaging and inspiring read; it is filled with existential reflections which not only deal with reminiscences of growing up, with relationships, and rites of passage, but with all the complexities of life, with unexpected encounters — not least with language ... Inspiringly, Irish Willow manages to catch quite a bit of the uncatchable mystery of being".

Irene Gilsenan Nordin, "The Uncatchable Mystery of Being: Chris Arthur's Irish Willow", Nordic Irish Studies, Vol.2 no.1 (2003), pp.144-146

"Arthur's artistry jolts the familiar; he navigates the contours of involuntary memory by revealing the minor monuments of habitual life. Indeed, in Arthur's imaginative grip the habitual is invested with the symbolic energy of the ritual ... Irish Willow transfuses the everyday object, place, event or relationship with a resonant historical or political valence ... [it] navigates the philosophical terrain between individual experience and the cultural milieu in which one is born and raised. By meditating on the caprice of individual memory and the intercommunal mobilisation of sectarian memory, Arthur signals a discursive or philosophical alteration in the learned or atavistic modalities of perception. Arthur's is at once a poetic, affective and sometimes chilling prism ... The collection is an exhilarating affirmation of the act of rumination, both in terms of writing and reading. Arthur's deft prose and lacerating meditative style provoke empathy, humour, disagreement and no shortage of self-reflection. Irish Willow confirms that the cadence of the suddenly unearthed image, metaphor or thought creates and reserves its own authority. Life and the manner in which we experience it are irrevocably sensual processes, and Arthur's essays remind us of the need to listen for the concatenations of life's fragile musicality."

Eóin Flannery, Irish Studies Review, Vol.12 no.1 (2004) pp.120-121

"In this second set of personal essays, Chris Arthur's unique Ulster voice continues to explore intersections of the local and the cosmic, the historical and the mystical, the personal and the natural. The essays ostensibly focus on mundane matters — willow pattern china, family history, gardening, taxidermy, a coffin table, photography, country walks, and much more — but whatever Arthur's declared subject, it is the drama of his questing personality that matters. As in his first collection, Irish Nocturnes, Arthur's manner of "falling through" surface meanings into a dense underworld of interpretations and contexts gives these prose musings their interest and significance ... Arthur's musings embrace a range of attitudes and questions. His is a post-religious consciousness, and there are moments here when Matthew Arnold or George Eliot, or even the early Yeats come to mind. But the driving energy of these essays bounces between the cold comfort of the "true" Buddhist scripture as a blank page and the unlimited wonder that heightened imaginative engagement reads into the universe ... Arthur has devoted much attention to the craft of the essay genre, and his use of short and long versions, personal and highly theoretical material, turn and turn about, challenges the reader to follow the contours of his thinking ... His insistence on metaphysical questions foregrounds his probing of how human consciousness engages with the deeper conundrums of being, yet these "portals into complexity and connection," as he calls his essays, are also portals into those personal forces that drive Arthur to write with such tenacity and persistence, with such ambition and sense of mission ... Arthur's essays have been widely published in American literary journals which are hospitable to creative non-fiction. Hubert Butler is his nearest kin in the field of Irish writing, a figure largely neglected for most of his writing life; it is to be hoped that the genre Arthur has chosen will not cause his unique body of work to be similarly neglected. These essays, like the first set, will repay repeated rereading. Arthur's capacious and lucid intelligence is matched by his ceaseless wrestling with the "landmass" of language to shed light where received ideas and expressions have conspired to conceal it".

Denis Sampson, Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, 30.1 (2004), 86-87

"Chris Arthur's essays belong to the central tradition of the essay in that they are at once intensely personal, meditative and engaged with the dynamics of their own world ... Arthur's central method is to lead us along subtle mental pathways from words to questions to symbols to new dimensions with the lightest of touches. His prose abounds with the liminal. His essays are elegant and stylish explorations that change direction, that should be read and re-read like haiku, that are virtually impossible to summarize and that take us, through a profound sense of the ordinary, into a world of loss and longings."

Bryan Coleborne, Australian Journal of Irish Studies, Vol.4 (2004), pp.343-344

"Sometimes Arthur's work almost looks as if it was the example Cynthia Ozick had in mind when she said that 'Essayists are a species of metaphysician: they are inquisitive — also analytic — about the least grain of being' (1988: xx). Arthur's 'grains of being' are invariably chosen from his Ulster upbringing and offer fascinating insights into it. However, it is his musings on time and space in a religio-philosophical sense, rather than accounts of some one particular time and place that invest his writing with the power it carries. Though rooted in the everyday, the real concern of the essays is with metaphysical questions that probe the fundamental nature of being. He wants to lead readers towards a sense of something mysterious/miraculous which he sees embedded even in the most mundane circumstances ... In Arthur's handling, the most trivial happening, the most mundane object, is shown to have undreamed of dimensions of significance. As James Rogers notes, "Arthur's favourite strategy is to take a familiar object and to peel back the many layers of meaning and association embedded within it (2001: 150) ... Though the books are undoubtedly of interest in terms of their local references and the insights they offer into the Irish psyche, it is not, in the end, their treatment of the County Antrim landscape that fascinates, but the way in which they unearth from it themes of much more widespread interest ... [Their] universality is achieved by focussing on the metaphysical rather than the mundane (but also by focussing on the metaphysical through the mundane); by showing that epiphany lies not in some remote sacral region, the preserve of formal religion, but at the heart of our everyday experience."

Mairtin Howard, "The Otherworld and the here and now: An Introduction to religious themes in Chris Arthur's essays", Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses, Vol.33 no.1 (2004), pp.71-89 (the quote is from pp.80-82)

"Arthur lets his thoughts range over the possibility and/or probability of life and all experience being connected to form a vast network, known as 'Indra's net' in Buddhist teaching ... The essays in Irish Willow, though taking their inspiration from quite different aspects of Arthur's life and background, are basically variations on the theme of connectedness ... The titles hardly hint at the direction in which Arthur's thoughts take the reader. Who would have guessed that 'Handscapes of the Mind' (pp.127-45) would lead from a meditation on memories of his father's playing Beethoven's piano sonatas, to outlines of children's hands on a wardrobe, to those of prehistoric cave dwellers, to language, to symbols, and then on to the Red Hand of Ulster? This essay stands out for the balance achieved between the sequence of ideas and Arthur's ability to express his feelings for his father ... Arthur opens his eyes and enables his readers to open theirs to see the variety and textures of the lives he writes about and how they were fashioned to a great extent by the history of Northern Ireland. He himself comes across as a thoughtful and imaginative person whose questioning mind enabled him to break out of his background for the larger worlds of East and West."

Honor O'Connor, Irish University Review, Vol.37 no.2 (2007), pp.574-577

“Chris Arthur is an Ulster-born, Buddhist-influenced, Scottish-educated former Irish game warden turned essayist now living in Wales. His first collection, Irish Nocturnes, received positive reviews on both sides of the Atlantic. Now he's back with a second volume of essays, Irish Willow, in which his personal meditations include both his memories of Northern Ireland and his philosophical musings. Arthur has been praised for breathing new life into the genre of Irish history, and for his simple, graceful writing. His essays are all about wildlife, and contemporary Ireland, and about exile, loss and personal identity.”

Grania McFadden, Belfast Telegraph, July 04 2008

Irish Willow has also received mention in less specialised publications, such as:

- The Library Journal and the Los Angeles Times Book Review (where it was flagged up in the "Discoveries" section, see the issue of Sunday March 17th 2002, p.15). As with Irish Nocturnes, there is also some web-based comment.

- Likewise it has been reviewed in Etudes Irlandaises. Danielle Jacquin's review is in Vol.28 no.2 (2003), pp.179-180.

Irish Willow can be bought from:

"It's as if, for those few thousand words, we are invited deep inside someone's mind."

Susan Orlean

Contents

- Foreword: Falling Through

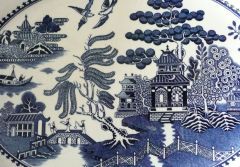

- Willow Pattern

- On the Face of It

- Table Manners

- The Cullybackey Fox-Weasel

- Takabuti's Tears

- Walking Water

- Transplantations

- Handscapes of the Mind

- Taxidermy

- Atomic Education

- Train Sounds

- A Tinchel Round My Father

The willow pattern design referred to in the first essay of Irish Willow.

A view of Muckish Mountain, Co.Donegal, seen from across the New Lake at Dunfanaghy, near the family farm of the author's ancestors. The great aunts who lived on this farm feature prominently in "Table Manners".

The shrine and flagpole at Windy Gap — in the Dromara Hills — referred to in "Takabuti's Tears".

The Legannany Dolmen, not far from Windy Gap.

Takabuti, the Ulster Museum's famous Egyptian mummy, lived around 2,800 years ago in Thebes. She was the daughter of Nespare and Tasenirit.

The railway station in the author's hometown of Lisburn, Co. Antrim. This station is the main setting for "Train Sounds".

Photographs of the author's father — pictured here — are the subject of "A Tinchel Round My Father".